3. ASSESSMENT OF PSYCHOSOCIAL WELLBEING OF LEARNERS

Psychosocial risks assessment at organisational level

This paragraph wants to highlight the concept of “positive psychology”[1]. This means changing perspective by shifting the attention from a corrective attitude towards a mindset of positive planning. The latter means to build those positive conditions that allow organisations and employees to thrive in the workplace.

Risk prevention strategies differentiate between primary and secondary prevention[2]. Primary risk prevention acts at the organisational level, particularly on the working environment and conditions. Secondary risk prevention acts at the individual level by educating how to manage and cope with hazards, risks and associated costs. The best approach is the integrated one, hence a balanced mixture of primary and secondary risk prevention strategies is needed.

There are some existing instruments derived from research in the field of applied occupational psychology that can help VET providers and employers to detect, assess, manage and prevent psychosocial risks at the level of the organisation. The five instruments below have been selected because more appropriate for the purpose of this paragraph, that is to illustrate the practical application of such tools. However, many equivalent instruments have been developed that can be applied to specific needs and circumstances.

SOBANE is a risk prevention strategy that involves four levels of intervention and the active participation of working staff[3]. The four steps, described by the European Working Conditions Observatory, are the following:

1. Screening: employers detect hazards and take action to reduce the associated risks.

2. Observation: the remaining risks are examined and discussed in more details.

3. Analysis: if necessary, an occupational health practitioner is required to provide ad-hoc solutions.

4. Expertise: in more complex scenarios, an expert is needed to solve a particular issue.

CANEVAS[4] is an instrument used for business analysis. The goal is to conduct a company stress diagnosis. It involves an initial overall assessment of the workplace in terms of risks and evidence of stress. It investigates the nature of work activities (e.g., tasks, role, autonomy, decision making, etc.), of the work environment (i.e., context, organisational structure, interpersonal relationships, etc.) and individual resources (i.e., family, personality, resources, health, etc.)

The Multidimensional Organisational Health Questionnaire[5] is a questionnaire-based tool that investigates indicators of organisational wellbeing such as environmental comfort, clear goals, competence valorisation, listening, information availability, conflict, relationships, problem‐solving, demands, safety, effectiveness, fairness and openness to innovation.

Both SUVAPRO[6] and the Finnish Institute of Occupational Health Checklist[7] are based on a checklist to aid observations with the purpose of screening stressful circumstances of a company, the symptoms of psychosocial risks and the resources for intervention.

Psychosocial risks assessment at the individual level

At individual level, when a stressor event occurs in the workplace, this might trigger a reaction of psychological, behavioural, emotional and cognitive nature. If the stressor event is not addressed promptly and becomes a recurring circumstance, the risk of long-term consequences is concrete in terms of adverse effects on mental and physical health, cognitive abilities and social behaviour. Similarly, applied occupational psychology can help to identify protective factors, coping mechanisms and counteractive measures that are beneficial in decreasing workers’ vulnerability to risks.

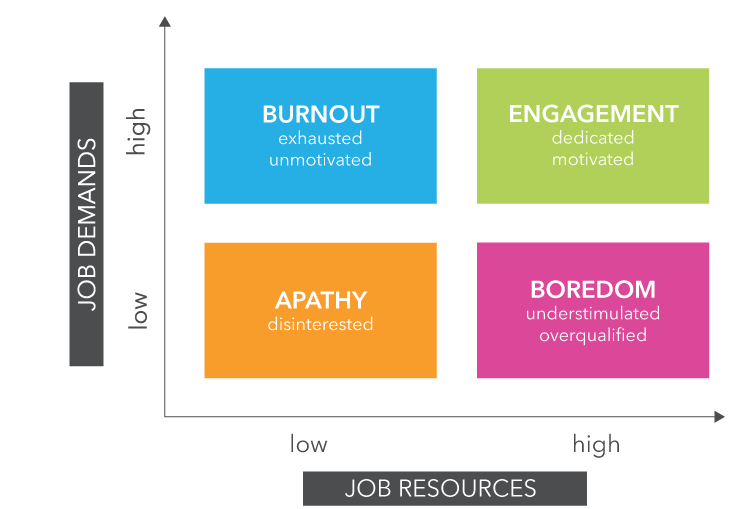

According to the job demands-resources model[8], it is important to remind that the impact of a stressor event depends upon a subjective evaluation of this event. Hence, the impact of such event depends upon the personal resources of an individual to manage and cope. According to this model, job demands refer to those elements that can be considered as a cost for the individual in terms of required physical, cognitive and emotional energy. On the other hand, job resources are those positive aspects associated with the organisation, social relationships and personal resources, that help to reduce the perceived job demands and/or to increase engagement/motivation.

Therefore, coping mechanisms can act at two levels. First, by decreasing the perceived job demands; for instance, by removing the individual from the stressor event. Second, by increasing job resources; for example, by conducting a cognitive restructuring of the perceived problem or through psychological counselling. Communities of practices can also help to increase one’s job resources by sharing experiences and best practices, thus developing resilience competences in a supportive and collaborative environment.

Figure 4 – Job Demands/Resources Model Chart[9]

Throughout the course of a VET placement, in order to assess the psychosocial risks for VET learners, there is the need for a defined methodology and practical tools. The ideal instrument does not require the administration by a psychologist practitioner and can be implemented by VET providers and companies to a wide range of working contexts. Some practical examples are direct observations, interviews and/or questionnaires, also through the Likert scale (i.e., the most widely used approach to scaling responses in survey research). Information and data collected can be both qualitative and quantitative.

The assessment tools can adopt different approaches to the subject matter and consider multiple dimensions deemed relevant to VET learners. Ideally, the tool should examine each of the following domains of psychosocial wellbeing: self‐esteem and self-efficacy, personal agency, secure relationships in the family, work related stress (i.e., job content, workload, work pace and work schedule), safe and consistent work environment, competent and responsible supervision and tutoring, contractual arrangements, social network and peer support, leisure time, emotions and somatic factors, chronic fear/anxiety and sense of hopefulness.

An alternative assessment tool[10] might use a different categorisation approach and examine the following five domains of psychosocial wellbeing:

1. Cognitive skills and cultural competence (i.e., intelligence, communication skills, technical skills, etc.).

2. Personal resources and social competences (i.e., secure attachments, positive peer relations, social confidence, sense of belonging, etc).

3. Personal identity and valuation (i.e., self‐esteem, feeling valued and respected, etc.).

4. Sense of personal agency (i.e., self‐efficacy, internal locus of control, positive outlook, etc.).

5. Emotional and somatic factors (i.e., work related stress, overall health, sleeping/eating patterns, concentration issues, chronic fear/anxiety, etc.).

The domains listed above can be distinguished in domains of impact on learners psychological functioning and domains of protective factors. Protective factors include secure attachments and relationships, personal resources, social competences, social network and peer support, competent and responsible supervision and tutoring, and leisure. Cultural values attached to the idea of a VET placement could either moderate or enhance psychosocial risks. Indeed, cultural beliefs and expectations of family members can influence learners’ perceptions and expectations of the industry placement, potentially having both positive/negative impact.

Beyond the domains of psychosocial wellbeing listed above, in order to gain a comprehensive understanding of the learner, the information collected should be analysed according to demographic characteristics (i.e., age, sex, ethnicity, migratory status), educational experience (i.e., enrolment, level, attendance, school performance, type of school, etc.) and work history (i.e., age starting work, duration, etc).

[2] Guglielmi, D. and Fraccaroli, F. (2016). Stress a Scuola. 12 Interventi per insegnanti e dirigenti. Il Mulino.

[3] Malchaire, J. (2004). “The SOBANE risk management strategy and the Déparis method for the participatory screening of the risks” International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health.

[4] Delaunois, M.; Malchaire., J.; Piette, A. (2002). Classification des méthodes d'évaluation du stress en entreprise. Université catholique de Louvain.

[7] Hurrell, J. J., Jr., Nelson, D. L., & Simmons, B. L. (1998). Measuring job stressors and strains: Where we have been, where we are, and where we need to go. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology.

[8] Bakker, A. and Demerouti, E. (2007). The Job Demands‐Resources model: state of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology.

[9] Prevuehr.com. Power of Control: The Positive Correlation Between Autonomy & Work Engagement. Based on Bakker, A. and Demerouti, E. (2007). The Job Demands‐Resources model: state of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology.